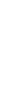

By becoming a member of FoundMyFitness premium, you'll receive the Science Digest every-other-week covering the latest in my exploration of recent science and the emerging story of better living — through deeper understandings of biology.

- Ketogenic diet, by replacing glucose with ketones as an energy source, lessens alcohol cravings among people with alcohol use disorders.

- Omega-3 fatty acids reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease-related death by up to 23 percent, especially in people with high triglyceride levels.

- Women see a 24 percent drop in premature death risk with just 140 minutes of weekly activity – half the time men need for similar benefits.

- Aging undermines the brain's capacity for maintaining working memory, with subtle declines in neuron activity and connectivity in the prefrontal cortex.

Most older adults experience some degree of hearing loss, yet few recognize that it may increase their risk of cognitive decline. A recent study found that nearly one-third of dementia cases over an eight-year period might be linked to hearing loss measured with a hearing test.

Researchers monitored nearly 3,000 older adults, aged 66 to 90, for up to eight years. All participants had normal cognition at the beginning and underwent a hearing test and a self-assessment of their hearing. The researchers compared the number of new dementia cases over time with each participant’s hearing status at the start of the study.

They found that up to 32% of dementia cases could be attributed to hearing loss. This link held true even for those with mild hearing loss. However, individuals who only reported hearing issues without a hearing test did not exhibit the same increased risk—likely because self-reporting often underestimates actual hearing loss. The proportion of dementia cases associated with hearing loss was highest among individuals aged 75 and older, women, and white participants.

These findings suggest that treating hearing loss, particularly when identified through a proper hearing test, could delay or even help prevent dementia in many older adults. A key driver of noise-induced hearing loss is inflammation, which is also linked with dementia. Learn more in Aliquot #90: Inflammation and the Early Seeds of Dementia — and Its Prevention

Plastics may be a hidden contributor to heart disease: chemical additives that disrupt hormone function and damage blood vessels. Evidence indicates that di-2-ethylhexylphthalate (DEHP)—a phthalate used to soften plastics—drives oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. A recent study found that this plastic additive may have contributed to more than 350,000 cardiovascular deaths worldwide in 2018.

To estimate the global burden of cardiovascular disease linked to DEHP exposure, researchers combined country-level cardiovascular death rates with regional exposure estimates. They calculated the number of deaths and years of life lost that were likely due to the chemical, drawing on published hazard ratios and biomonitoring data.

They found that DEHP exposure contributed to 356,000 cardiovascular deaths in 2018—around 13% of heart-related deaths among adults aged 55 to 64. Exposure varied widely by region. The Middle East and South Asia had the highest levels of several DEHP metabolites, including mono (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate at 19.460 micromoles per liter—six times higher than levels in Europe. Africa also showed high concentrations, including the highest recorded level of mono (2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate at 65.452 micromoles per liter. The Middle East, South Asia, and Africa bore the greatest exposure burden, while Europe had the lowest.

These findings suggest that chemical additives in plastics pose a serious threat to cardiovascular health, especially in regions with growing plastic production or weaker environmental protections. As plastic products break down, they shed tiny fragments known as microplastics, which carry considerable health risks. Learn more in this episode featuring Dr. Rhonda Patrick.

Even a minor fall can cause a life-altering fracture for women with osteoporosis. Stronger bones can mean the difference between maintaining independence and facing long-term disability. A recent study found that combining high-intensity interval training (HIIT) with daily vitamin D supplements more than doubled the gains in bone mineral density compared to each intervention alone.

Researchers enrolled 120 sedentary women aged 30 to 50, all diagnosed with osteoporosis. They randomly assigned participants to one of four groups: a control group, a vitamin D group (800 IU per day), an exercise-only group (16 weeks of HIIT), and a combined group that did both. Before and after the intervention, researchers measured bone mineral density of the hips and spine and markers of bone turnover in the blood.

They found that the group combining HIIT and vitamin D supplementation showed the greatest improvements in bone mineral density at the hips and lumbar spine, with a 3.2% improvement in hip bone mineral density, surpassing the 1.5% increase in the HIIT-only group and the 1.2% increase in the vitamin D-only group. Blood levels of calcium and osteocalcin increased the most in the combined group, while bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (a marker of bone breakdown) decreased. Improvements in bone mineral density were linked to higher calcium and osteocalcin levels and lower body mass index.

These findings suggest that pairing HIIT with vitamin D supplements boosts bone strength in women with osteoporosis, helping to slow or even reverse bone loss during midlife. Learn more about the effects of HIIT on bone density in this clip featuring Dr. Martin Gibala.