Blue light exposure and the importance of darkness at night as it related to depression

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The Omega-3 Supplementation Guide

A blueprint for choosing the right fish oil supplement — filled with specific recommendations, guidelines for interpreting testing data, and dosage protocols.

In the modern world, there is an evolutionary mismatch concerning light exposure. Many people are indoors during the daytime where they are not exposed to bright light, while artificial lighting allows light exposure during the night. Light exposure is essential for entraining a variety of bodily rhythms such as cortisol release and cytokine production. Moreover, research shows that bright light therapy is helpful in the treatment of non-seasonal depression. In this clip, Dr. Charles Raison discusses how exposure to light during the day and maintaining a dark environment at night is important in depression management.

- Rhonda: All of it. And the other thing we didn’t talk about was, and you kind of mentioned, you alluded to it with this evolutionary mismatch, you mentioned, you know, that the world that we live in today is much different. We’ve got all these artificial lights, you know, we’re...

- Charles: It’s a big thing.

- Rhonda: Yeah, our light exposure has totally changing. You know, some of us are in offices all day and we’re not exposed to bright light during the day, then we go home at night with all these lights on. You know, so it’s kind of, there’s a mismatch there. And I do know that there’s, I think I sent you a couple of studies, and one was showing that bright light exposure was able to even help treat people with non-seasonal depression or.

- Charles: Oh, absolutely. Yeah, there is some nice data on that.

- Rhonda: Yeah.

- Charles: Absolutely.

- Rhonda: What I was kind of trying to make was the link between cortisol and the bright light exposure.

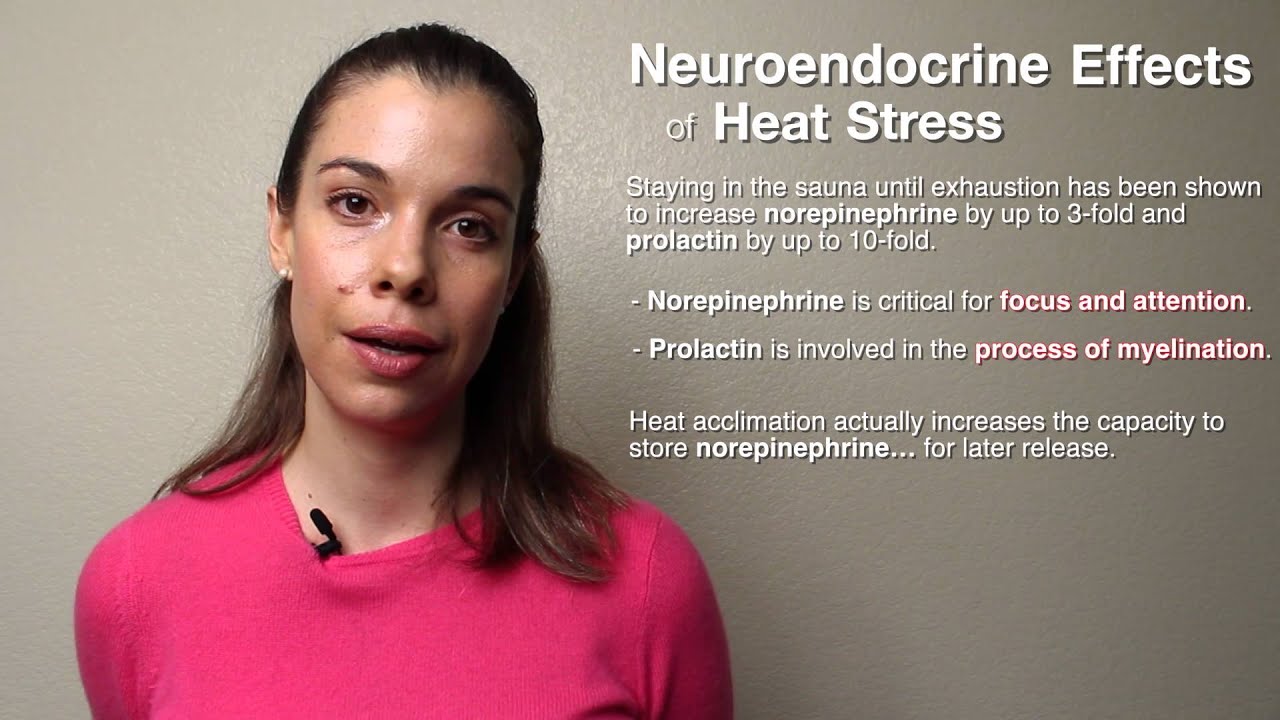

- Charles: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Because of course, you know, that’s what entrains to a large degree of cortisol rhythm, and probably cytokine rhythms too. They also...

- Rhonda: Right. Yeah.

- Charles: Absolutely. There’s another example of this idea that humans evolved to, if not need to function optimally with certain types of inputs. If you say, “Why do they function optimally with those inputs?” It’s because across a couple of million years that’s what they got, and so they evolved to function optimally with those inputs. You know, the reason we like bright light in the morning and dark at night is because for like, until fairly recently, since the creation of the world, mornings were bright and nights were black. And so we, you know, we marry ourselves to those conditions because evolution is always trying to optimize the organism to the environment, that’s the challenge, right? So we optimize to that mixture of light, but then we also have a, sort of an evolutionary mandate to compete with each other, to be productive. And so all of a sudden, you invent things like lights, and now you can stay up all day and night.

- Rhonda: And work.

- Charles: And work, because that’s also a human mandate, right? I mean, we’re these ultimately social creatures, and so we get ourselves in these double binds where these mandates, you know, one mandate is if you see somebody’s sweet, eat it immediately as much as you can, because it’s rare and it’s huge calories, and that’s great. So if that’s true, then maybe we should just invent nothing but sweet stuff. That’s so awesome, but now we’re killing ourselves with sweet stuff, so now we need to, you know, renounce. So you always like you get these sort of things where one mandate in the human world interacts problematically with another, and light is a classic example of that.

- Rhonda: Yeah, it is. And the fact that, you know, the circadian rhythm is regulated largely by light, also by food intake as well. But the cortisol take on it, you know, cortisol is a hormone that changes like 25% of the human genome. Many of those genes involved in inflammation...

- Charles: Absolutely, that’s a huge inflammatory.

- Rhonda: Yeah, exactly. So it totally makes sense that these two are, they’re interconnected. You know, having just bright light exposure there is one study where exposing humans to like 10,000 lux of bright light for seven hours a day lowered their cortisol response during the rising phase when it’s usually the highest. So obviously, it was a anti-inflammatory sort of, or depressive, I guess immunosuppressive effect as well because you’re not having as high of a cortisol response, yeah. But another thing that just so many humans don’t realize that could also be playing a role in their depression, the way that they’re responding to emotional stimuli, and all these things. So I personally, we, my husband and I have optimized, try to optimize to the best of our ability our light exposure. So we have these lights in our house called Philip Hue, which basically, they can change color. So blue light is what, you know...

- Charles: It’s what you want early in the day, and not what you want at night.

- Rhonda: Not at night. So at night we have it all set where you can time them so that the shuts off the blue light and it turns on red light. So we have all these red lights around our house that come on.

- Charles: Oh, cool.

- Rhonda: Yeah. And it really, really makes a difference. I mean, you get tired, you know, because you start making melatonin, and so the sleep onset is much earlier than if you were to have regular, old blue lights. Yeah. And then we have, you know, apps on our phone and our computer called lux, sorry, f.lux, which then also tones down the blue light so your computer screen isn’t emitting the blue light, yeah. But the lights around the house are really cool. They’re kind of expensive, but really worth it.

- Charles: And you have them all around the house?

- Rhonda: We have them in every room, yeah.

- Charles: What are they called?

- Rhonda: In the kitchen. Philips Hue.

- Charles: H-U...

- Rhonda: I’ll send you, H-U-E.

- Charles: Okay, send that after.

- Rhonda: I will, yeah. It’s really cool. They do all sorts of colors. They do purple, blue, orange. But we go from the bright, blue to red, yeah. So that’s what we’re using them for. And then the bright light exposure early in the morning, like having, going outside for 30 minutes, or just making sure you have to light in the house.

- Charles: Even on the cloudiest day?

- Rhonda: Yeah.

- Charles: You get like 5,000 lux on a cloudy day. You cannot, yeah, it’s just this...

- Rhonda: So, you know, on a cloudy day you get like...

- Charles: Oh, you get a lot, compared to just sitting in your average room.

- Rhonda: And do you know how long, like can people just use 30 minutes or an hour? Because it’s hard.

- Charles: It is. I tell people 30 minutes.

- Rhonda: Thirty minutes.

- Charles: I mean, yeah, there’s no doubt that the light boxes really help a lot of people, and not just seasonal people. So there’s another example. There’s an interesting example of a simple technology recapitulating natural conditions that optimize human emotional wellbeing. Now, the other thing that I’m convinced is really important is dark. There’s a whole biology on dark.

- Rhonda: Like during the time when it’s supposed to be dark?

- Charles: Yeah. Because even a little bit of light absolutely screws up melatonin release, you know, blue light, mostly. I mean, that’s why it’s really smart to do this. But, you know, I mean, we cannot now, the first academic paper I ever was called “The Moon and Madness Reconsidered,” about why the moon was associated with madness in ancient times, making an argument that the moon was essentially a light source that activated manic episodes. Because, you know, sleep deprivation is such a powerful driver of mania. But as part of that work, I did this massive research on the history of lighting, and it is so interesting, you know. Like for instance, in ancient Rome, Rome was so dark at night that you could go out into the biggest street in Rome and you wouldn’t see your hand in front of your face, unless the moon was out. I mean, it was just pitch black. People take everything in, and it was just total blackness. London was pitch black, you know. There was a massive prostitution business that was run on the London Bridge. We know this because Boswell, you know, Boswell, the guy that wrote the biography of Samuel Johnson, recorded all those dalliances. And, you know, he’d be out there doing it on the bridge. I actually went back and matched the dates of his prostitute things with the phases of the moon in the 1760s, and he was always doing it at the dark of the moon. It was fascinating. I mean, London, the greatest city on earth in that time, was so dark that you could do that. This is in the 1760s. There’s a guy named Tom Ware, he’s retired now, but he was sort of the king of the circadian stuff. I mean, he was at NIMH, the National Institute of Mental Health, and he actually took... He did this great study, and in particular he took this one just impossibly bipolar person, stuck him in the dark for 12 hours every day for a year or so, and just profoundly fixed the guy. Now, darkness is another example actually, of an ancient spiritual practice. So one of the first bizarre sort of tantric heavy duty Tibetan Buddhist practice, is something called the “Dark Retreat,” where people go into utter, complete darkness for 49 days straight.

- Rhonda: Forty nine days, wow.

- Charles: That’s the length of time that they believe, that’s the maximum length of time between reincarnation.

- Rhonda: And are they also in silence as well? Silence and dark.

- Charles: Silence, except for a couple of times a day when people slip, they’ve got some mechanism now for slipping food under the door, people checking them.

- Rhonda: But they’re not talking to anyone?

- Charles: No. And they start hallucinating like mad.

- Rhonda: Wow.

- Charles: The point of that is utter sensory deprivation. The point of that then is to, from their perspective, the point of that is to recognize that the whole world can arise from the creation of their mind, and so they realize that this world is also sort of insubstantial. I mean, at least that’s my understanding of the spiritual. But isn’t that amazing that something like dark can also be appropriated for spiritual practices? Now, whether it would have any therapeutic potential is kind of unknown, but it’s on my bucket list, not to do 49 days, but to go. I’ve got an invitation to go check it out, yeah.

- Rhonda: Wow.

- Charles: Very famous television journalist is going to come.

- Rhonda: It’s hardcore.

- Charles: It’s hardcore.

A wavelength of light emitted from natural and electronic sources. Blue light exposure is associated with improved attention span, reaction time, and mood. However, exposure to blue light outside the normal daytime hours may suppress melatonin secretion, impairing sleep patterns. In addition, blue light contributes to digital eye strain and may increase risk of developing macular degeneration.

The body’s 24-hour cycles of biological, hormonal, and behavioral patterns. Circadian rhythms modulate a wide array of physiological processes, including the body’s production of hormones that regulate sleep, hunger, metabolism, and others, ultimately influencing body weight, performance, and susceptibility to disease. As much as 80 percent of gene expression in mammals is under circadian control, including genes in the brain, liver, and muscle.[1] Consequently, circadian rhythmicity may have profound implications for human healthspan.

- ^ Dkhissi-Benyahya, Ouria; Chang, Max; Mure, Ludovic S; Benegiamo, Giorgia; Panda, Satchidananda; Le, Hiep D., et al. (2018). Diurnal Transcriptome Atlas Of A Primate Across Major Neural And Peripheral Tissues Science 359, 6381.

A steroid hormone that participates in the body’s stress response. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone produced in humans by the adrenal gland. It is released in response to stress and low blood glucose. Chronic elevated cortisol is associated with accelerated aging. It may damage the hippocampus and impair hippocampus-dependent learning and memory in humans.

A broad category of small proteins (~5-20 kDa) that are important in cell signaling. Cytokines are short-lived proteins that are released by cells to regulate the function of other cells. Sources of cytokines include macrophages, B lymphocytes, mast cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and various stromal cells. Types of cytokines include chemokines, interferons, interleukins, lymphokines, and tumor necrosis factor.

A mood disorder characterized by profound sadness, fatigue, altered sleep and appetite, as well as feelings of guilt or low self-worth. Depression is often accompanied by perturbations in metabolic, hormonal, and immune function. A critical element in the pathophysiology of depression is inflammation. As a result, elevated biomarkers of inflammation, including the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, are commonly observed in depressed people. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioral therapy typically form the first line of treatment for people who have depression, several non-pharmacological adjunct therapies have demonstrated effectiveness in modulating depressive symptoms, including exercise, dietary modification (especially interventions that capitalize on circadian rhythms), meditation, sauna use, and light therapy, among others.

A critical element of the body’s immune response. Inflammation occurs when the body is exposed to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. It is a protective response that involves immune cells, cell-signaling proteins, and pro-inflammatory factors. Acute inflammation occurs after minor injuries or infections and is characterized by local redness, swelling, or fever. Chronic inflammation occurs on the cellular level in response to toxins or other stressors and is often “invisible.” It plays a key role in the development of many chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

A hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle in mammals. Melatonin is produced in the pineal gland of the brain and is involved in the expression of more than 500 genes. The greatest influence on melatonin secretion is light: Generally, melatonin levels are low during the day and high during the night. Interestingly, melatonin levels are elevated in blind people, potentially contributing to their decreased cancer risk.[1]

- ^ Feychting M; Osterlund B; Ahlbom A (1998). Reduced cancer incidence among the blind. Epidemiology 9, 5.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Get email updates with the latest curated healthspan research

Support our work

Every other week premium members receive a special edition newsletter that summarizes all of the latest healthspan research.