Fatty Liver

Episodes

Dr. Guido Kroemer discusses immunology, cancer biology, calorie-restriction mimetics, aging, and autophagy.

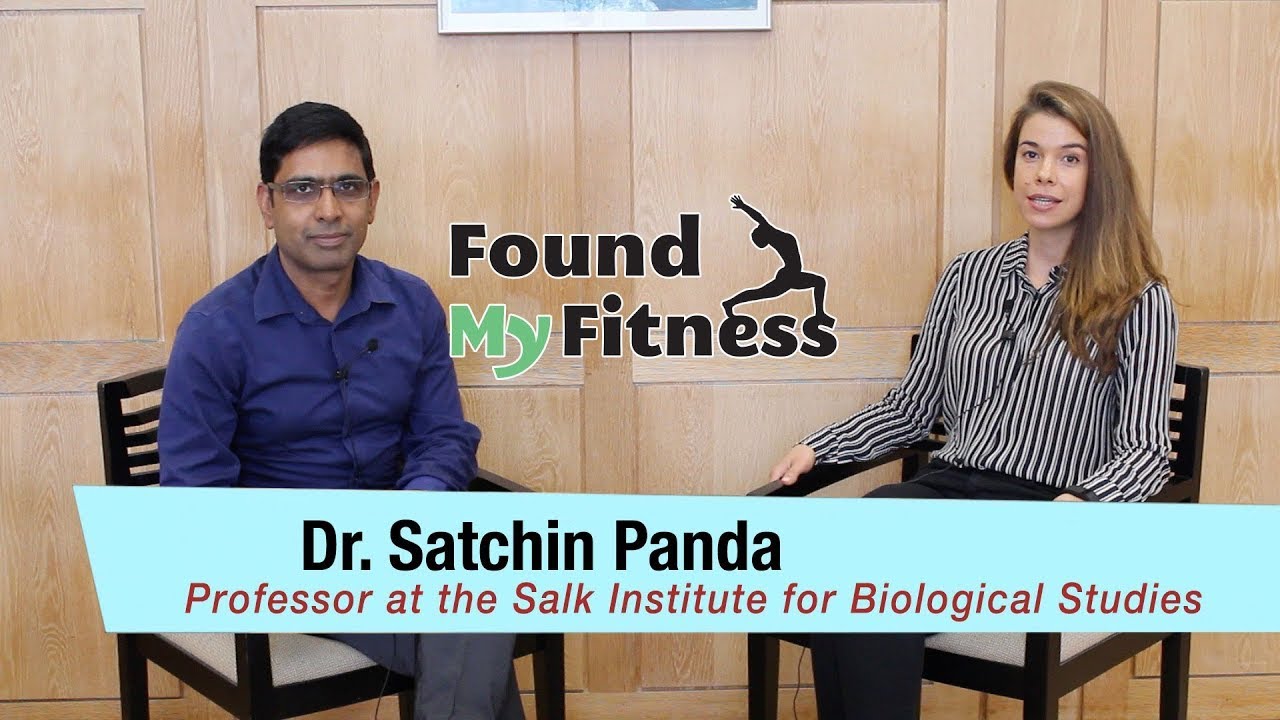

Dr. Satchin Panda discusses the roles that fasting, time-restricted eating, and circadian rhythms play in human health.

-

Aging Nutrition Cancer Podcast Fasting Multiple Sclerosis Autophagy Video Triglycerides Fatty Liver Time-Restricted Eating ProteinDr. Guido Kroemer discusses immunology, cancer biology, calorie-restriction mimetics, aging, and autophagy.

-

Dr. Satchin Panda discusses the roles that fasting, time-restricted eating, and circadian rhythms play in human health.

Topic Pages

-

Berberine

Berberine is a plant-based compound with pharmacological actions that share many features with metformin.

-

Ultra-processed Foods (UPFs)

UPFs are formulations of mostly cheap industrial sources of dietary energy (calories) and nutrients plus additives that have negative effects on human health.

News & Publications

-

Fructose-containing beverages increase free fatty acid production in the liver, a marker of metabolic disease risk. www.sciencedaily.com

Metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), represent a major public health burden. Dietary factors such as excess sugar intake are associated with greater metabolic disease risk; however, it is unclear how different types of sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose, or sucrose) differentially impact metabolic health. In this report, researchers investigated the effects of sugar-sweetened beverages on fatty acid synthesis, blood triglycerides, and hepatic insulin resistance in healthy males.

Following the consumption of glucose, the pancreas secretes insulin into the bloodstream so that insulin-sensitive organs such as the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue can transport glucose into their cells. Excess sugars are converted to fats in the liver via a process called de novo lipogenesis and then stored in adipose tissue; however, as fat levels in adipose tissue rise (i.e., overweight and obesity), fat accumulates in the liver leading to the development of NAFLD. Fructose, the main sweetener found in sugar-sweetened beverages, does not require insulin to be absorbed and is preferentially taken up by the liver, accelerating NAFLD development independent of weight gain.

The authors recruited 94 healthy lean males (average age, 23 years) and assigned them to consume beverages sweetened with moderate amounts of either glucose, fructose, or sucrose (a sugar that contains both glucose and fructose) in addition to their normal diet for seven weeks. The beverages contained an amount of sugar found in about two cans of non-diet soda. The researchers assigned a fourth group of participants to consume their normal diet with no added sugar-sweetened beverages. They assessed fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis by the liver and whole-body fat metabolism.

Daily consumption of beverages sweetened with fructose and sucrose, but not glucose, led to a twofold increase in the production of free fatty acids in the liver. Fructose intake did not increase triglyceride production in the liver or whole-body fat metabolism. Participants from all four groups consumed about the same amount of calories, and while body weight tended to increase for all groups, this relationship was only statistically significant for the group consuming glucose-sweetened beverages. Glucose and insulin tolerance did not change with sugar-sweetened beverage consumption.

The investigators concluded that consumption of beverages sweetened with fructose and sucrose increased free fatty acid production in the liver. While they did not observe changes in other metabolic markers such as insulin tolerance, they hypothesized that the alterations in fat production by the liver pave the way for metabolic disease development.