#101 Dr. Andy Galpin: The Optimal Diet, Supplement, & Recovery Protocol for Peak Performance

This episode is available in a convenient podcast format.

These episodes make great companion listening for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

High-level performance isn't just for elite athletes — it's a blueprint for anyone who wants to feel, move, and live better.

In this episode, Dr. Andy Galpin — Executive Director of the Human Performance Center at Parker University, trusted coach to world champions, Olympic gold medalists, Fortune 500 executives, and government leaders — breaks down the science of peak performance into practical, actionable steps anyone can use.

From the right way to train and fuel your body, to supplements that actually move the needle, Dr. Galpin shares insider strategies refined at the highest levels of sport and performance — and shows how they can elevate your fitness, health, and longevity, no matter where you're starting from.

-

Training fasted—are the mitochondrial benefits worth it?

-

Is intermittent fasting killing your gains?

-

Carbs before resistance training—fuel or fluff?

-

Caffeine cycling—smart strategy or outdated myth?

-

Rhodiola rosea—fatigue fighter or placebo?

-

Beetroot, citrulline, arginine—do nitric oxide boosters work?

-

Beta-alanine—why the tingles might be worth it

-

Can you trust what's in your pre-workout supplement?

-

Tart cherry juice—recovery aid or overhyped?

-

Is glutamine the immune booster athletes need?

-

Can simply soaking in water accelerate recovery?

-

Why pre-bed cold exposure might improve sleep

-

Heart rate variability vs. resting heart rate

-

Is your bedroom's CO₂ buildup sabotaging your sleep?

Nutrition for Performance vs. Longevity

"If you are eating like a high-performance athlete, for the most part, you are also eating for longevity. The only big fundamental difference might be caloric balance. That is the top layer. But other than that, it is pretty similar."- Dr. Andy Galpin Click To Tweet

Dr. Galpin frequently addresses questions about diets optimized for either health and longevity or performance. These seemingly different goals actually share significant overlap. Eating like a high-performing athlete is eating for health and longevity. Central to both objectives is:

- An emphasis on protein intake (quality and quantity).

- Consuming a variety of foods and colors to obtain micronutrients.

- The importance of dietary fiber and calorie management.

- Carbohydrate and fat intake adjusted to individual goals and preferences.

The primary distinction between eating for health versus performance typically lies in total caloric intake—athletes may require a surplus for peak performance, whereas moderate caloric intake might be more suitable for longevity.

-

Optimal Performance Nutrition

-

Diets for longevity and performance share core traits—high protein, fiber, and micronutrient diversity—with caloric balance and timing being key points of divergence.

-

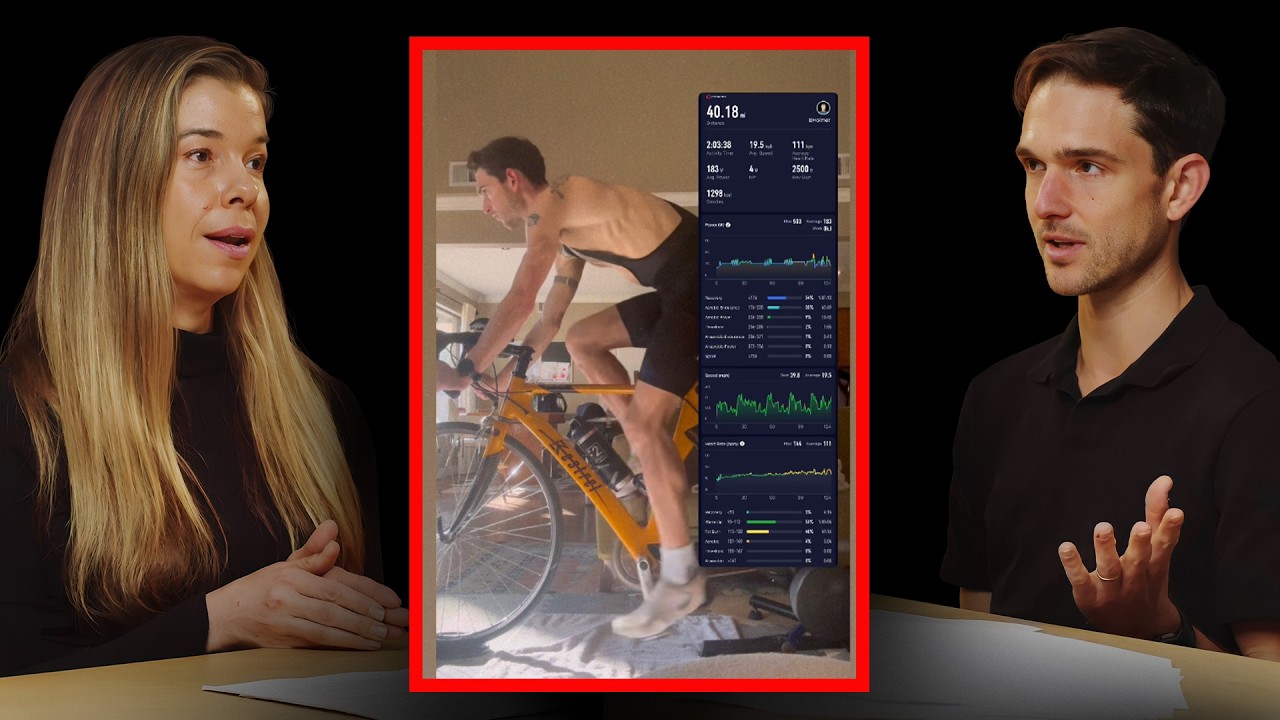

Fasted zone 2 cardio may enhance mitochondrial adaptations and fat oxidation, but personal preference often outweighs marginal gains in practice. (Galpin study) 1

-

How much food do you need before morning strength training? Small, fast-digesting meals—like a banana, yogurt, or granola—can optimize performance when time is limited.

-

Why nutrient timing isn't critical for the average exerciser

-

Whether following a 16:8 time-restricted eating schedule leads to muscle loss remains an open question. In well-trained adults on a hypercaloric diet, 8 weeks of supervised strength training showed similar muscle gains—but greater fatigue—compared to eating throughout the day. 1

-

Dr. Galpin suggests fatigue in the 16:8 TRE group may have been reduced with more carbohydrate availability during training. However, cramming 600–700 grams of carbohydrates into an eight-hour window proved taxing on the gut, revealing practical challenges with implementing TRE in a hypercaloric context.

-

TRE may subtly impact energy levels—participants in a training study reported increased napping despite unchanged sleep duration.

-

How carbohydrate intake before exercise is not always necessary, except for endurance athletes and high-frequency trainers.

-

Carbohydrate timing matters most for performance and recovery during high-intensity or frequent training—mistimed intake can impair energy levels, while rapid post-exercise replenishment accelerates glycogen restoration.

-

Ultra-endurance athletes may require up to 100 grams of carbohydrate per hour, but maintaining intake becomes difficult as taste fatigue and texture sensitivity build over time. Eating carbohydrates soon after a workout helps restore energy faster—especially if you're going to train again later that day or the next.

-

When is post-exercise carb intake truly essential?

-

Training and nutrition strategies for endurance events should mimic the actual race to avoid body distress, applying the same pre-, mid-, and post-fueling approaches.

-

Carb supplements vs. whole foods—what do elite athletes actually eat?

-

Dr. Galpin proposes that fueling strategies should be individualized—fat and carbohydrate needs vary by context, and true metabolic flexibility is built through training, not diet alone.

-

Metabolic flexibility—how the term got hijacked

-

The real test of metabolic health—why skipping a meal shouldn't break you

-

Are anaerobic and aerobic systems truly separate?

-

Pre-sleep protein ingestion may increase overnight muscle protein synthesis, especially in individuals struggling to meet their daily protein intake. 1

-

Twelve weeks of post-training whole egg ingestion improved strength, testosterone, and reduced body fat more than egg whites in trained young men. 1

-

Rhonda Patrick and Andy Galpin prefer whole foods over protein powders, citing taste, digestion, and minimal processing—but acknowledge powders can be useful for convenience and hitting protein targets.

-

Fat timing—overlooked or irrelevant?

-

Fat quality matters more than type—balanced intake from minimally processed, whole food sources supports endocrine, cellular, and overall health, while excess and poor processing are where the problems begin.

-

Supplements for Exercise Performance

-

Micronutrients are generally covered by a varied diet, but supplementation may be warranted depending on individual needs.

-

Magnesium deficiency is common among athletes due to increased losses and higher demands, underscoring the need for high-bioavailability intake through diet and supplements.

-

The problem with magnesium blood tests

-

Magnesium insufficiency, prevalent in over half the U.S. population, is often missed in standard blood tests — with up to 50% lost from bone by older age, this hidden depletion may contribute to osteoporosis, and active individuals may require 10–20% more due to sweat and urination losses.

-

Why the magnesium RDA might not be enough

-

Magnesium supplements, once notorious for causing GI distress, have become safer and more effective over time. Forms such as bisglycinate, citrate, and threonate are accepted as beneficial for both athletes and non-athletes, despite past apprehensions about other types like oxidates.

-

Do magnesium supplements really aid recovery?

-

Magnesium threonate has shown benefits for sleep 1

-

Omega-3 supplementation—is the AFib risk real?

-

Omega-3 supplementation before a period of disuse can halve muscle atrophy, suggesting muscle may be sensitized to amino acids by omega-3's presence.

-

Why "performance anchors" matter more than supplements

-

How Dr. Galpin prioritizes supplements to correct physiological insufficiencies, viewing them as foundational tools for enhancing performance, recovery, and cognition before adding ergogenic aids.

-

Iron loss from physical impact, including heel strike hemolysis, affects more than just menstruating women — but iron is not an innocuous supplement, and proper assessment is essential.

-

How caffeine's impact on performance is about more than a fat-burning effect, but enhancing workouts, changing training volume, and altering mental motivation.

-

Caffeine may boost performance even if you don't feel it — objective tests like time trials or total work output are the best way to measure its true effect.

-

Can music measurably enhance workout performance?

-

Rhodiola rosea may improve muscular endurance and mitigate stress responses, without the known stimulating effects of caffeine.

-

Beetroot, citrulline, arginine—do nitric oxide boosters work?

-

Chronic intake of beta-alanine significantly boosts repeated high-intensity cardiovascular performance — like in CrossFit — by increasing muscle carnosine levels, aiding in buffering against exercise-induced acidity.

-

Creatine dosing, ranging from 3 to 20 grams per day, enhances athletic performance without notable adverse effects — gradual increase from a lower starting dose is a common strategy.

-

Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), including topical forms like PR lotion, can boost high-intensity performance — drawing on its ability to increase alkalinity and buffer exercise-induced acidity. This offers a practical, fast-acting option for athletes, especially those sensitive to gastrointestinal side effects.

-

Can you trust what's in your pre-workout supplement?

-

Despite suggestions of mitochondrial and longevity potential, taurine's benefits for performance enhancement remain unconvincing, according to sports scientist Dr. Andy Galpin.

-

Is too much caffeine killing your performance gains?

-

Excessive antioxidant supplementation, including high-dose vitamin C and E, may disrupt exercise adaptations, with effects shaped by timing, dosage, and whether the goal is performance or adaptation. 1

-

Is it okay to use NSAIDs to manage delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), or do they blunt training adaptations and limit muscle gains?

-

Tart cherry juice, rich in polyphenols, potentially eases muscle soreness and improves sleep, showing promise for bodybuilders who may benefit from its dual recovery attributes.

-

Glutamine, an amino acid valued in both clinical and athletic settings, shows potential in supporting immune function, gut health, and brain recovery—specifically post-concussion or under caloric restriction.

-

Hydrolyzed collagen powder, when paired with vitamin C and taken prior to exercise, shows potential for improving connective tissue health and promoting skin, tendon repair — a useful addition for athletes and those with soft tissue injuries.

-

Does glucosamine chondroitin actually help joints?

-

Recovery Tactics

-

Recovery from training initiates adaptive improvements through inflammation, immune signaling, and physiological stress, with sleep, nutrition, and subjective perception playing critical roles. Methods such as gentle movement, thermal therapy, and compression tools help reduce muscle soreness by promoting blood flow and tissue oxygenation.

-

The most important recovery metric

-

How increased blood flow accelerates muscle repair

-

Why persistent soreness might mean your fascia's at fault

-

Can compression boots genuinely speed recovery?

-

Compression boots mimic the benefits of active recovery, enhancing circulation and reducing muscle soreness post-exercise.

-

Can simply soaking in water accelerate recovery?

-

When is sauna a better choice than extra miles?

-

Can localized heat preserve muscle during downtime?

-

Cold immersion timing—muscle recovery vs. blunting gains

-

Why pre-bed cold exposure might improve sleep

-

Heart rate variability vs. resting heart rate

-

Why respiratory rate predicts stress better than resting heart rate

-

Are you overtrained—or just overreached?

-

Hormones and overtraining—what's the real link?

-

Sleep

-

Does training harder mean you need more sleep?

-

How to know if you're getting enough sleep

-

Sleep trackers

-

Hydration timing—the key to uninterrupted sleep?

-

Why your wind-down index matters

-

Is your bedroom's CO₂ buildup sabotaging your sleep?

-

Are nasal allergies quietly wrecking your recovery?

-

Sleep hacks—what actually works?

Rhonda Patrick: Hey everyone, I'm super excited to be sitting across the table from Dr. Andy Galpin, who is the director of the Human Performance Center at Parker University. Andy and I have been corresponding for at least the last 10 years. I'm pretty pumped to have this conversation. He is an expert in muscle physiology, but also has published a wide range of, I would say, exercise physiology-related topics from, you know, muscle health to nutrition to recovery. He also coaches athletes, Olympians, MMA fighters, just all around got a lot of experience and the science behind it. So I'm really excited to have this conversation with you today, Andy. I mean, you and I have talked about, you know, a lot of things via, you know, X and Twitter at the time. I think email as well. So thank you so much for coming on the show.

Andy Galpin: It's just, I can't even explain how much of an honor and a pleasure this is. I've been telling you for a long time now how stoked I am about this, and my wife is tired of hearing of it, so I'm finally excited to get here and do it.

Rhonda Patrick: Well, today it's kind of interesting because, you know, you've got this vast publication history in muscle biology and exercise physiology, but I'm kind of taking you in a direction where you've also published and you have a lot of knowledge regarding nutrition, supplements, recovery. I'm super interested in the role of those in helping people sort of meet their fitness goals. And when it comes to nutrition, I mean, this is obviously a field that's constantly, you know, there's no agreement ever, whether we're talking about performance or longevity.

Andy Galpin: Sure.

Rhonda Patrick: But, you know, there's a growing number of athletes and people that are like myself, which are, I would say, committed exercisers, that I'm very interested in health, not as much in performance, although I'm becoming a lot more interested in performance these days. But I'm interested in longevity, for sure. I mean, that's my primary interest. And so there's people kind of trying to figure out what kind of diet they could, you know, what kind of diet they could eat to sort of meet their performance and longevity goals, if that's even possible. Is that something that you've thought about?

Andy Galpin: Yeah, I get the question of performance versus longevity or health or nutrition a lot. And I think, as you've done so well over your career, there are tenets that are going to agree and then there's going to be distension. And so I think it's easiest maybe to frame this as what are the flags we can put on both sides of this equation? Known obvious yeses and obvious noes, right? So if you want to live your longest, healthiest life, number one, we're all going to agree on probably five, seven, maybe eight different things. And if you were to look... I'll just do it this way. If I said, okay, great, because we deal with these clients. I deal with high-performance athletes, as you mentioned, and we have a lot of our clients that are like you. They're not athletes, never were, do not care, but they're wanting to live their longest, healthiest life. And if I threw their diets in front of you, I'd be stunned if you could tell me which one was for which person. I don't think you'd have any chance, right? So you'd say, what's that going to look like? We're going to center around protein, right? You've talked about that endlessly. It's going to be high and high quality. We're going to have a lot of variety of foods. We're going to have a lot of variety of colors. Turns out micronutrients, vitamins, and minerals are pretty important, right? Like your entire career. We're going to have some attention paid to fiber. Caloric intake will be managed. We're going to distribute carbohydrates and fat in some way that helps them hit their needs and goals and personal preferences. We could go down the list. But the easiest way to think about it is, how much overlap is there? Almost all. What are the small differences between these performance and longevity goals? Well, depends on what type of performance. So we're talking about a lot of caloric expenditure. Are we talking about a power event? Then, yeah, we're going to find some differences. And we can chop that up all day if you want to know exact numbers and hours. But the reality of it is, both of those people, performance, longevity, you have to manage calories one way or the other. You have to do all the other things. It's not that different. You can make some arguments of maybe you can get away with certain things. If you're not interested in performance, you can do some different things with food timing, food frequency. You can play with some different stuff where you wouldn't want to do that with a high-performance athlete. So there's a lot of fun differences with those things. But at the highest level for the average person, if you're eating like a high-performance athlete, for the most part, you're also eating for longevity. Only big fundamental difference there might be caloric balance. That's the top layer. But other than that, it's pretty similar.

Rhonda Patrick: I was kind of thinking that was going to be your answer. I'm very interested in the intermittent fasting, time-restricted eating, training while you're fasted, depending on the type of training, because it's something that I do for certain types of training. You like to train fasted.

Andy Galpin: Well, I like to train fasted if I'm going for a 30-minute run, zone 2 kind of run. And the reason I do that is because, I mean, this was years ago, I read a meta-analysis, and maybe I would love to hear your updates on the literature because I know that you've been keeping up with it. But there was a meta-analysis looking at people that were training fasted, and if they were doing endurance type of aerobic exercise training, and they trained, they were training, it was like less than 60 minutes. It was like less than an hour, right? And this is like a zone 2 kind of below the lactate threshold type of training. Then they had better adaptations in mitochondria, mitochondrial enzymes, obviously like fatty acids being oxidized. So whereas if they trained when they were fed, again, it was less than an hour, some of those adaptations were blunted somewhat. And for me, it was like, oh, well, I kind of want those adaptations. So I do like to train a little bit fasted. Now, I don't do hour-long runs anymore. That was like a thing of my past for me. I do my strength training. I do not like to do fasted at all. I have to have like something like a banana. I have to have some glucose or something. So I'd love to get your take on training while fasted.

Rhonda Patrick: Right after that, I'm also dealing with a guy preparing for a 900 mile hike. So that context is important because as I'm answering questions like this, all these avatars are in my head, and I'm thinking, what is true for person one, two, and three, and what is true for the other person who doesn't exercise at all? If something is not consistent across those four, then I have to modify and contextualize the answer. So when it comes to training fasted, great. If you are going for an event like you're talking about, and you feel better when you do it, that matters to me in that particular context more than the physiological benefit, because the physiological benefit is not fake, it's just not huge. So is it more beneficial for your mitochondria? Yes, potentially, but if you look at the amount, it's not that much. Now, if you liked it or didn't care, fine. But if you're like, I hate it, my performance is worse, I don't like it, I don't feel good, then we actually don't do it. And so my first layer answer to all that is, number one, what are you actually performing best in? What are your personal preferences? Are you training in the morning? Are you training in the evening? All these other factors that are now, again, contextualized are my true answer. And I hate to be wishy-washy on that, but that's the most honest answer because I deal with a lot of people with different goals and different scenarios. So the science can lead us in one direction, but the actual layering on top of what would I really recommend a human do, that in this scenario matters more. So if you look at the research very specifically on fasting exercise, always depends on the type of exercise. You mentioned you were really careful about saying, I'm under 60 minutes, right? I'm under 60 minutes. I know you're aware that answer will change. What am I optimizing for? Performance? Am I optimizing for feeling better that day, more focused that day? There's so many different reasons why one would exercise that you have to answer all those questions and figure out, well, what lever am I trying to pull here? So do we ever take somebody and say, hey, you need to start doing your endurance work in the morning, fasted? I can't think of many times we've ever done that. But if somebody shows up with that, we don't have any reason. We're not going to pull them off it either.

Rhonda Patrick: What if someone says, I'm interested in fat adaptation, I'm interested in mitochondrial health, and I'm not an endurance athlete. I'm just, you know, these are my recovery days, I do strength training on other days, these are my recovery days, so to speak, in a way. Then would you still kind of, what are your thoughts on that? So you mentioned mito adaptations aren't, it's not, it's a subtle difference. But what about lipolysis? Like what about, you know,

Andy Galpin: Yeah, so the way that we would frame this is we need more information on them to determine whether or not that's going to actually matter for them. So if they're saying, okay, I want to enhance fat burning, I want to enhance oxidative capacity, great. Well, we actually need to look at their capacity for metabolic flexibility. We need to test that. I need to see that number, right? If you're just saying you want more, I'm going to say more from where? Like, where are you currently at? I don't know. Well, then we don't know if we have anything to actually gain here. So we could do that intervention, and I don't know if it would do anything for you. If you're already pegged on that, if your mitochondria are already functioning very high, if your ability to utilize fuel independent of food is strong, then we're not going to get anything from that. If you're really weak in that area, then we would get something from it. So our first answer is data, right? We have to run some objective tests. If you don't want to do that or can't do that, you want to give that a try, sure. Like, fine, it's probably not going to hurt much in the short term. So go ahead and do that. So my answer to somebody who asks that question, I want to optimize mitochondria, okay, great. Starting off with fasted cardio is not the place we would go, but we might use it eventually if you can do a whole bunch of stuff, and we could do this objectively. Okay, when you go out and train, how do you feel if you don't eat before? Oh, I feel terrible. Then that's an easy litmus test. There's way more we get into in detail. I wouldn't only ask that question, but that's how we'd actually think about it. So it could be everything from yes to I'm not super worried about it. If they're really, really stoked to do it, I'm probably going to say yes just for that fact alone. But I don't necessarily think you have to do that to have healthy mitochondria, if that's another way to answer the question.

Rhonda Patrick: What about people that are doing strength training, resistance training first thing in the morning, and they don't have a lot of time? They're getting their kids ready for school, it's like they want to feel with something. What's the best option?

Andy Galpin: Personal preference in terms of feeding or not feeding. The literature would be fairly clear here, and I'd say our personal experience would match that. Some people are fine, some people are not. If you want to go just practical recommendations, a banana and a protein shake is super easy, a little bit of yogurt maybe and granola. We have a lot of our athletes that will train in the morning, and that's a really common thing. Some granola, yogurt, maybe honey, maybe some berries, small six to eight ounces, right, really small servings, 300 calories, maybe 50 grams of carbohydrate, some protein, 10 to 30 grams, depending on their physical size. Remember, some of our athletes are 115 pounds, some of them are 350 pounds, so numbers vary. So personal preference, but yeah, the recommendations would be things like that. We don't have too many athletes or clients that we'll intentionally ask them to not eat before they train, like we sort of talked about, but the easy, quick, just get out the door stuff, that's what we're going to lean on, very simple, easy digesting, small amounts of food, probably not as much as your full breakfast, but those things will tend to work pretty well.

Rhonda Patrick: I think athletes are less interested in that, and people that are more interested in body recomposition, they're wanting to lose fat, gain muscle, are more interested in, okay, well, perhaps they're that kind of person that their liver glycogen takes more hours before it depletes, and then it's like, well, if I then eat before my run, then I didn't fully deplete the liver glycogen, so they're not going to be perhaps undergoing lipolysis and oxidizing fatty acids for energy. So what about people that are interested in, that are fit, they're not really athletes, but they're exercisers, they're interested in just sort of fat loss, body recomposition?

Andy Galpin: The acute timeframe pre-, mid-, post-exercise for those people probably doesn't matter that much. It really isn't going to have a huge impact. What will matter is the days and weeks, the total caloric expenditure throughout the day. This person, if you're training in the morning, you probably have at least 24 hours to recover, even if you're training hard every single day. Most of the time, when we get really specific about nutrient timing, it's because a lot of our clientele are training twice or more a day, that's when timing really is critical, whether you're talking about timing of fat, protein, carbohydrates, so when we hear people say things like, oh, timing doesn't matter, for the average person, it's not a huge deal, but for some, it really significantly matters. But what you just described is not. You're talking about the person who is just training once. There's a ton of recovery time. So what you have before the workout doesn't matter a huge amount. Whether you have it immediately post doesn't matter a huge amount. The total in throughout the day. The only caveat is actually what you asked a little bit before, it's personal preference, I don't feel as well. Great, that's the context, it's not the physiology or the biology that's mattering there, it's now personal preference or objective data that says we

or it makes your sleep worse, or it's better for everything. Whatever combination the answer is going to be, I don't really care. But that's the full context people have when they make dietary decisions. So that's what we did. We took people that were very well trained, and we did eight weeks of strength training with them in the lab, supervised, all that. Already, again, previously well trained, men and women, college age, as normal. We did biopsies, we did muscle imaging, we did questionnaires, we did sleep stuff, we did blood, we did a bunch of different things. And ultimately what we wanted to see was, okay, we're going to put them all at the same protein load, and we're going to put them in caloric excess. So hypercaloric, not hypocaloric. We know the answer what happens with TRE if you're trying to lose weight. What happens if somebody actively trying to gain muscle? So that's the very unique twist of this. And it was super interesting. The take-home message was it didn't matter a ton. As long as you hit your numbers, the results were basically the same across both groups. So standard four, five, six feedings a day versus TRE. Now we actually doubled down on the question because we actually made the people train in the TRE group in the morning, and then they had to wait at least an hour before they fueled afterwards. So they trained fasted. They didn't recover with protein or anything like that immediately afterwards, and they stayed in that state until the afternoon. So even despite of that, it didn't significantly compromise muscle growth or performance or really anything else. We saw some subtle differences. The TRE group actually looked like it didn't gain as much body fat because you're going to do that when you go hypercaloric, right? Especially if you're well trained, you want to add muscle, you're going to bring some fat along for the route. I don't know if it was enough of a difference, and I spent a lot of time in that data set. I don't know if that's a real finding, to be honest, or if that was just a little bit of an artifact. The counter to it was as time went on, fatigue got higher in the TRE group. Legs got heavier. Performance in the legs started to decline. Again, so much so would I suggest TRE is going to be bad? No, no, but it was like, okay, I think there's something happening here. I think potentially if we were to change the study design a little bit and give them fuel closer, that would have made it not exactly sure. We would have to run a separate study design for that. If you torture the data a little bit, you might find some subtle differences between the two groups, and they were statistically significant in effect size and all those things there. But looking at it from a real practitioner perspective, my general take-home was it didn't matter a ton. If you're trying to maximize leg strength and maximize leg growth, I probably wouldn't go to 16-8 TRE. But if you have other reasons to do it, you're still going to get gains. They still got stronger. They didn't get as strong. There are some other issues that happen, but either one of them works.

Rhonda Patrick: But do you think, again, if they were a lot, I mean, most people, after they're done strength training, they eat within an hour. Like I immediately am getting protein in me because I just, my body wants it. So do you think that maybe would negate some of the performance deficits that you found?

Andy Galpin: I think it honestly was more of a carbohydrate issue.

Rhonda Patrick: Carbohydrates.

Andy Galpin: Yeah, I think that was the bigger issue because they were going so long without carbohydrates and they were training so hard and they were doing the same workout multiple times per week. I just think over time, we were also progressing them. So they were being tested every time they came in the lab and the training got harder, right? Like traditional progressive overload. I don't think they—I wish we had actually biopsy data for their muscle glycogen levels. But if I had to suspect, I think that that was starting to leak down. And I just think the legs were getting—we would say just getting heavier over time. Like it just wasn't handling the volume because that's actually what happened too. The volume that the TRE group did started to come down at the end. They just couldn't do as much volume as the other group could do.

Rhonda Patrick: At the end of a workout, not like at the end of the eight.

Andy Galpin: No, at the end of the eight weeks. Because we tested them pre, mid, and post.

Rhonda Patrick: When were they working out? Morning or evening?

Andy Galpin: Morning. Yep, they're all working out fasted. They're doing strength training fasted. Yeah. So the bottom line—this study will be published soon, depending on when this comes out, it may already be out any day. I'm stunned it actually hasn't. You can gain muscle on a 16-8 time-restricted eating schedule, even if you're doing the training fasted. There are ways to do 16-8. You can stop eating earlier and not have to be fasted in the morning, right?

Rhonda Patrick: Congratulations. This is great. This is a great study. You sent it to me, I can't wait to read it.

Andy Galpin: Well, so actually, that's super interesting, because when I looked at this, I was like, man, I think that just is the better approach. Maybe if they would have done their fasting in the evening, afternoon—there's a bunch of other arguments we could make that that's better anyways. That would be a really cool follow-up. And I'd be willing to bet they wouldn't have had such indirect markers of fatigue over time. They just didn't have fuel for a really long time. I can also tell you these things behind—and this is like the veil of people that, when you run actual studies, you can make comments about things that aren't in the paper. The people had a really hard time with the carbohydrates. That was the complaint. And so when you had a whole bunch, because some of these people are at 600, 700 grams of carbohydrate a day, and you got to get that in an eight-hour window, GI was just destroyed. A lot of people were like, man, my stomach is just blowing up from 600 grams of carbohydrate. Could you imagine eating 200 grams of carbohydrates, a couple hours later you got another 200, another 200. It was just a lot.

Rhonda Patrick: Was it so high because you were doing this hypercaloric? Because I mean, most people aren't doing that many carbohydrates unless they're like endurance athletes.

Andy Galpin: Yeah, well, we have some big people, right? So if you're 110 kilos and you've got to be hypercaloric and you're at six grams per kilogram body weight, those numbers get high fast. So in order to get there, that stuff got there. Even the protein got a little tough as well. So we didn't see—I wish we would have had more subjective questions in those areas, but I would say it was just hard for those people to hit their numbers. Most of them got there, but they're just like, whoa, I just wish I had another hour. Give me another two hours. Could I get 50 grams of this protein a little bit earlier? That'd make my life so much easier. So I just think from a practical perspective, it was harder for them to follow, it was harder for them to hit their numbers waiting the whole day than to start and hit it in a caloric surplus. So if you're not in a caloric surplus, different equation here. If you're in a caloric deficit, different equation here. But for people that are pre-trained, pretty well-trained, and they're actively trying to get bigger and stronger, it wouldn't be the first approach I would take. But it's still plausible. Clearly it worked. They still got benefits from it. But switching the order I think would be cool.

Rhonda Patrick: Would you say that if they were, let's say they were in a slight caloric deficit, still getting their protein, meeting their protein needs, would they be still gaining muscle, you think?

Andy Galpin: I don't think it would have gained as much. It would have gained some, right? If you look at, like, again, all of Graham's work and a lot of that hypercaloric state stuff, sometimes they gain muscle. It can happen. But can they gain it at the same rate as when you add more calories? I don't think so. And I don't think so because in our particular program, the training program was really aggressive. They were training hard for really well-trained people. I don't think the recovery would be there. I just don't think it would be there.

Rhonda Patrick: When did they stop eating, and how was their sleep affected?

Andy Galpin: So we let them choose their window. So some of them came in and trained at like 7 o'clock in the morning because they want to start their eating window at 10, right? But they're college kids, so most of them trained like 10, 11, 12 o'clock in the morning. And then they would start their eating windows between 1 and 2 o'clock in the afternoon, something like that, depending on if they work or whatever. So we let them shift a little bit. The time domains had to be the same, but we didn't make them start at noon, depending on their life schedule. Sleep didn't really change that much. I wish we would have had some of our newer sleep technology. We could have really objectively looked at it at the time; we just had basic questionnaires. What we did notice is the perceived fatigue and naps increased over time in the TRE group. So again, a little inclination there of saying I think fatigue was setting in more. Some of that didn't land statistically significant, but you start to see multiple things in the same pattern, and you go, all right, if we run a follow-up study there, that might be interesting to focus on.

Rhonda Patrick: Why is it important for people to have carbohydrates before they're doing strength training?

Andy Galpin: You don't have to. If you can get away with it, you're fine. It's not the thing we're super concerned about. Depending on where you're at, if you can get through it, if your total caloric intake throughout the day is fine, if your carbohydrate intake throughout the day is fine, and depending on how often you're strength training, if you're the kind of typical person who's training the same body part on non-consecutive days, then carbohydrate pre-exercise is not a big deal. It's totally fine. You can get away with your strength training. It'd be a personal preference. Again, if you're training, though, the same muscle group on multiple days or multiple times per day, that's when the carbohydrate timing will matter most. You can have it before—generally people feel better with it, performance is usually better, but it's not always.

Rhonda Patrick: Or, or if you're someone that is on more of a hypocaloric diet, if you're trying to lose fat or perhaps maintain your weight, you're kind of really watching your calories, then perhaps you're not having a huge total caloric—totally caloric intake per day—that you might want to have carbohydrates in that.

Andy Galpin: We will generally, as just a high-level rule, try to get more of our calories around training, period, regardless of what we're doing, regardless of what type of training, regardless of the person. As a first-level thing, that's our preference. We want to either do it pre, mid, post. In your example there, if we're trying to bring calories down, we're going to go somewhere else if we can. It doesn't always work that way; people don't always like it. But that is our default position: yeah, we're going to do more calories in and around the training to support it. I want better performance. You perform better, you get better adaptations. That's generally how we look at it.

Rhonda Patrick: What about people that are more endurance-type athletes? They're out running, you know, 10, 15 or more miles, or biking, cycling, biking. What about those individuals?

Andy Galpin: Different equation now, right? So whether you talk about strength training or even endurance training, but as you said earlier, like you're talking sub-60 minutes at kind of a moderate to low intensity, carbohydrate before training for most people is not going to matter that much. Now you're talking about something different: really high-intensity exercise for a prolonged amount and/or moderate exercise for a longer amount, right? So we'll define longer by plus 60 minutes. Now you will very often see performance improvements with carbohydrates. That said, we have some of our people, some of our friends—a good friend of mine that I will never stop giving him the business on this one—Cam Haynes.

Rhonda Patrick: Oh yeah, Cam's great.

Andy Galpin: The worst performance nutrition you could just possibly dream of, right? Like, he will intentionally not eat and drink water and then go run 18 miles, right? And you're just like, what are we doing here, right? I've made the argument, like, I will PR him in every race he's ever done if he would just let me—if he would just follow what I tell him to do. But he refuses. So you can do these things. This is not a matter of it's impossible physiologically, but are you going to get your best out of it? Probably not. Carbohydrates before exercise, probably three or four hours before exercise if possible, if you're trying to maximize performance, generally looking at something in the neighborhood of 50 to 100 grams of carbohydrates. That's a huge plus/minus range there. Three or four hours before, we're generally looking at starches, slower digesting, give it time, not a big spike. Some people we will tinker with 30 minutes before, something in the neighborhood of 50, 60 grams of carbohydrates, maybe a little bit more. Some people, though, deal with a glucose double whammy if you do that, so you've got to be careful. What I mean is, if you take a whole bunch of fast-responding glucose, things that get into your bloodstream really quickly, right before you start exercising, insulin starts pulling glucose down, muscle starts pulling it as well, and so blood glucose actually dips. This is like, I had a banana and honey right before I started my race, and then I got two miles in and I felt like death. Like, okay, you had two mechanisms at the same time that are independent, that are bringing it down, and blood glucose actually dips quite a bit until the liver has a chance to kick in and bring it back to normalized. So you'll feel that response pretty often, so you've got to be really careful with easy-digesting carbohydrates right before the event and depending on how long it's going to last. But those are rough numbers to start with. In the exercise itself, the numbers you're going to see here, somewhere in the neighborhood of 60 grams up to 100 grams of carbohydrate per hour, which is—if you want to maximize performance, you'll see the data will show you like 80 plus, 80 to 100 grams.

Rhonda Patrick: What kind of carbohydrates? We're talking—you don't want that easy stuff, right?

Andy Galpin: No, now you want the fastest possible, because you're in a race, right? You're moving, right? This is when the goos and packs and things hit in, so you're trying to smash it in there as much as you can. I actually just had a guy named Jordy Sullivan, a dietitian in Australia. He was just on my podcast, and he actually coached a guy named Ned Brockman. And Ned did a thousand-mile race on a track, so he ran on a track for a thousand miles. I think it took him like 11 or 12 days, something like that, to finish.

Rhonda Patrick: Did he—I mean, how was—where the sleeping…what was the sleeping—

Andy Galpin: The sleeping situation?

Rhonda Patrick: Sleep on the track, right?

Andy Galpin: Yeah, he would just lay down and crash for a little bit, and then he'd get up and just run again, and he just kept going. Jordy went through the exact details, exactly what he fed him, the amounts, the concentration. And when you get into things like that, when Michael's getting ready for this 900-mile hike thing, 60 to 80 to 100 grams of carbohydrate per hour is awesome in the lab. I put you on a bike and you're in my research facility—those are the numbers that work. But when you cross over into humans, you start getting really tired of goo. You don't want to taste sugary drinks anymore. And so when you get past a couple of hours of exercise, then you actually have to start really paying attention to texture and flavor profile and mouthfeel, because that stuff starts to matter, and you can't hit those numbers. They're just not realistic. So if you're going to try to do something like this, pick your poison in terms of the carbohydrate source—this is the fastest sugars—but if you're going for more than a couple of hours, you've got to really think carefully about, are you sure you're going to like that taste of that for six hours, because you probably won't.

Rhonda Patrick: It's just incredible. I can't believe people do things like that. What about carbohydrate replenishment after a long endurance-type of workout? Do you think that's important to replenish the glycogen stores?

Andy Galpin: Depends on what you had starting with. So did you feed before, or did you not? That is automatically our context. If you fed before, then we don't have to worry about as much directly after. If you're fasted, we've got to worry about more. The other context we have to pay attention to: again, what's our total caloric intake, what's our carbohydrate intake throughout the day, and when are we going to train again? Some of our folks, again, training multiple times per day, we are going to go absolutely out of our way to get 100 grams of carbohydrate post-exercise if it's a hard training session. That's a rough number. Again, that number scales up and down with physical size and caloric expenditure, things like that. If you're going to get on a plane and drive and you're going to do something else for the next two days, carbohydrate post-exercise—the amount doesn't matter—it's not a big deal. You're up against a race of replenishment time. If that matters, you want to, again, look for 100-ish grams of carbohydrate pretty close to finishing. Unlike protein, timing matters. The faster you get that carbohydrate in, the faster you will replenish muscle and liver glycogen. Protein, as you've covered many times, timing, anabolic window, not a big deal at all. But carbohydrates are different. You've got to repeat that performance again soon, faster, more, better. If you've got a lot of time, then your recovery window is plenty; then you're going to be fine.

Rhonda Patrick: Or even if you're just training for a race, right? If you're training like every day, you're probably going to want to get that replenishment in right away.

Andy Galpin: Well, in that case, actually, that's a great point, because it's not only necessarily just about recovering for your next workout, but you actually need to train that system. One mistake people make when they do endurance events like that is they will forget to mimic the race in training. So then when they get into training, they try to do something they haven't done before, and their bodies can freak out. This is when you get a lot of GI distress, when you get a lot of your tapering, and you know, the week before, all of a sudden your performance is down, and you're like, what's going on? Well, you're doing something different now than you were doing the last eight weeks. And so yeah, I would actually strongly encourage you to treat your practice races like your real race. So do your pre-, mid-, post-fueling strategies in preparation for that, so then when you show up, your body's like, yep, this is exactly what we do. This is exactly how we handle people for the Super Bowl, for world championship events, for the Olympics. You try to make those big events where they're so incredibly important and there's so much pressure and stress, that you want to make it feel like a normal practice. This is just what we do. So while most of you aren't going to be on that stage—I get it—when you go run that first 5K, that's still going to be a really, you're going to be really excited, and it's going to feel like that. Your body is going to know, wow, this is something I care about, or you go and you finally get to surf that wave that you've been wanting to do or whatever the thing is.

You've been wanting to go after. The thing you can control the most is making your day feel like you've been training. It's a normal process. This is what we do. Your body is going to know, wow, this is something I care about. Or you go and you finally get to surf that wave that you've been wanting to do, or whatever the thing is, you go on that hunt that you've been wanting to go after. The thing you can control the most is making your day feel like you've been training. It's a normal process. This is what we do. This is

Rhonda Patrick:

Andy Galpin: Everything from, again, I tanked, I bombed, I failed out, to I had my best performance ever. To kind of go back to the original question about eating for longevity versus performance, now we're kind of talking about here. Oh man, we're on question one still.

Rhonda Patrick: Well, no, I just kind of wanted to circle back because if we are talking about someone that is racing, right? They're competing, they're trying to PR, they're, you know, all of those things. Then the carbohydrate sources that they're eating aren't going to be what I'm eating. I'm not going to be, I'm certainly not going to be chugging the goo, but like the fast, like during like intra workout, right? While you're racing or even perhaps like you were saying right before, you know, eating the quick, like the stuff that's going to spike your blood glucose quickly isn't typically stuff that people that are eating for a longevity type of, like my carbohydrate sources are typically vegetables, you know, fruits that have a food fiber matrix. Most of the time, I mean, some fruits can hit your body a little quicker than others, like grapes, for example. But, you know, most of the carbohydrate sources are more complex carbohydrates.

Andy Galpin: Yeah, so fair point. This is that small sliver difference at the end, right? So again, if we were to look at your, we actually have probably, I don't know, five females right now that we're coaching that are plus around your body size. So we'll make just equivalence to you and those individuals. We take both your diets for you and all those different girls that are in different sports. They're going to be almost identical, right? So they're going to be heavily focused on vegetables and starches and fruit and all those things. What would that difference be? Well, okay, some of them post training might do a powdered glucose source. So we might give them a carbohydrate supplement. We might use a Vitargo or something like that, where it's like a scooped carbohydrate where you're probably never having that. You're not having it throughout the day. You're not having it pre and post your workout. You don't need 60 grams of carbohydrate. That's easily that. So that would be different, right? But what are they going to have post workout? I don't know, watermelon. They're going to have things that you're probably eating too. Do we have a little more liberty with them to add some more grapes? Sure, but you could also probably eat grapes too. You would just take something else like out or move it around or you would have more protein when you have the grapes or whatever different strategies we do. It's really small the amount of goos and powders and things like that that we're doing. We're going to eat 95% of their calories as whole real food. You've got a little bit of supplements on the end and things like that, but we're not going to spend too much time with low quality foods, even for those individuals. I want them eating real whole healthy foods. So that is a really small difference, I guess. So yeah, in some of those situations, for the most part, your diet and their diets would be very identical.

Rhonda Patrick: So fat often gets overshadowed by protein and carbohydrates. Where does fat come into the equation of meeting your fitness goals, whether you're an endurance athlete or strength training or not necessarily an athlete, just someone who's interested in being healthy and exercising and looking for the longevity aspects of diet and exercise?

Andy Galpin: Yeah, so I would say, I mean, you positioned it pretty well. Most people start with protein, lock that thing in, and then you'll play with carbohydrates and fat as a way to adjust the overall caloric intake. And because we know the role of carbohydrates in exercise performance, we will usually go to that second, and then fat gets the third consideration. Like, okay, fine, whatever calories we have left, we backfill with fat. And as long as your fat isn't too low and it's too low chronically, then you're not going to really run into too many issues with having insufficient amount of intake of fat, dietary fat. That said, this is something I've changed my tune on a lot, right? Like I come from the classic exercise physiology academic background, and all those people are carbohydrates first, carbohydrates second, third, fourth, and like fat was always shunned. And I don't think I believe that as much anymore. I also, we've experienced a lot. A lot of the people we worked with, they're fine on moderate to low carbohydrates, even high exercisers, non-athletes, but they train a ton. You're talking about guys and girls running 60 miles per week, right? Like real high energy expenditures in terms of performance, and they're at 100 grams of carbohydrate a day. They're not in ketosis at all. They're not even trying to be, but they just like are fine at 150 grams a day or 200 grams of carbohydrate a day, right? For 120 to 190 pound like individuals, kind of at that, just as some frame of reference for numbers there. In that case, their fat intakes are way higher and they're fine. We're not seeing any performance decrements, they're not having a hard time recovering, their sleep isn't going down, like sex hormones are fine. So I actually have seen enough evidence now anecdotally and empirically being like, I think actually you're fine there. I think you're okay. If you're giving yourself, if your endogenous recovery is sufficient, I think you're going to be just fine there. So what we do with carbohydrates and fat for that person you're describing is we let personal preference drive us a lot, right? We also will change it just so that you can have some dietary changes. Like fat tastes delicious. It's really hard, it's really bland when you don't get to have a lot of fat in your diet. So sometimes we'll bring carbohydrate down for a while and let them have more fat if we need to manage calories. We don't generally see that much for the average person. Like we don't see that many consequences performance wise. So I don't think most people are going to have this huge like, oh my God, I'm not recovering anymore. If you're doing a normal amount of exercise, I think you're going to be just fine.

Rhonda Patrick: Some people think if they're eating a high fat diet, low carb diet, and they're doing endurance type of exercise, they're more heavily biased towards endurance training, that they're going to be more fat adapted, they're going to be more metabolically flexible, and their mitochondrial adaptations are going to be superior.

Andy Galpin: I would not support that statement. I would disagree with that. This is a great one. So the term metabolic flexibility has been hijacked. And the way that it is described now colloquially is not what that phrase ever started to be, and it's not what that is intended to be. It's so crazy because metabolic flexibility has got turned into maximizing fat burning. It's supposed to be metabolic flexibility, which means you have the ability to run the whole gamut. I get it. If you pluck the average person off the street, they're probably less likely to be good at burning fat than they are carbohydrate. So on aggregate, we probably need to get more people better at burning fat. I'm with you on that one. But metabolic flexibility is not just maximize fat burning. Those are not the same thing. And that's how people will often describe that. If you go too hard on one side of the equation, you'll see a whole host of adaptations that compromise the ability to do the other things. That's not metabolic flexibility, that is still specialization. You're just specializing in the other side of the equation. If that's what you want to do, fine. We're all for it. But we generally like to see people truly flexible on both sides. So if you want to go higher fat in your performance because you feel better, you like it, great. If you can demonstrate no issues, we're all for it. But if we're doing it for a theoretical idea and you don't actually have information behind that, then we're not going to support those ideas. So you want to go higher fat? Great. We have had some people where we've tinkered around with some number of people. Actually, we've tinkered around with different things. We try a higher fat diet, and they actually do perform better. So we stay with that, right? Even independent of any metabolic flexibility data we've got on them, great. We're going to stay on that. And then we've had others that are the opposite. So these are these really long-duration endurance folks that are out there, and they just don't do well when carbohydrates get low. And so we have to have room for both of those realities. Some people will perform better on a higher fat diet for more fat-oxidizing, lower-intensity things, and some will just do a lot better on those. And to finish up the point, I'm talking about long-duration endurance events that are both fast and slow. So if you look at, to be ridiculous, like we were talking about Cam earlier, you look at Rob, producer, these guys are under 2.5-hour marathon times. Cam's higher, but Rob's at 2.5-hour. He's fast. He's going to be burning, I don't know, I don't have metabolic data on him, but 70% to 80% carbohydrate in the marathon. So that's a long-duration endurance event, but that is not a fat-burning event. That is a carbohydrate game, right? If you want to run a marathon fast, that is a carbohydrate game. If you want to run a really, really long one and you don't care about speed, you're still going to burn a boatload of carbohydrates. But now we can afford to go slower with more fat oxidation. And so when we say endurance, there's also another level of question. It's like, okay, fast endurance or just endurance for the long term?

Rhonda Patrick: Well, yeah, it does answer the question. It's basically like, no, you don't have to be eating a higher fat diet, isn't necessarily going to make you better at burning fat.

Andy Galpin: Oh no, definitely not. I certainly think that when it comes down to that metabolic flexibility exercise, again, when you're doing a lot of exercise, you actually are becoming more metabolically flexible through exercise, in my opinion, than anything else.

Andy Galpin: Actually, I think the one thing that's kind of interesting here that does get left, the way that we think about metabolic flexibility is more of an innate human skill rather than an exercise performance one, such that I think we all should have the ability to go for six hours and not have any food and still perform cognitively. You shouldn't be hangry and cranky because you missed lunch. Now you're not super resilient. Whether this is a metabolic flexibility issue or not, if that's happening consistently with you, I would say we have some room to grow with metabolic health likely, right? You should probably be able to go 24 hours and maintain cognitive function and maintain physical performance. If you've ever, you've done some fasting, like longer fasting stuff, right? You should be able to not eat any calories for 24 hours and still exercise, right? You will not deplete really of very much anything. If you're the person who is the like, I can't do anything, I skipped lunch or didn't get to breakfast, then I think we have some stuff to do. But this is more of like, you have probably are lacking some innate physiological skills that are going to help you in multiple ways. But past that, the metabolic flexibility thing is, again, not often packaged correctly in my opinion.

Rhonda Patrick: What do you think about, so I've had Marty Gabala on the podcast talking about high intensity interval training and how obviously when you're doing, a lot of people think when you're like doing HIIT that it's like this all, I'm only burning glucose, right? If I'm doing zone two, I'm only burning fat, I'm only oxidizing fat and using mitochondria and they don't realize there's actually a lot of gray going on. Like you're doing high intensity interval training types of exercise, you're, yeah, you're going above the lactate threshold, you're using glucose as fuel, but you're also still using your mitochondria, right?

Andy Galpin: There are many things to say about poor understanding of metabolism is how I'll say that. There is no way to fully metabolize carbohydrate without oxidation. You just can't, right? Like you can run through and we can do it, and it's probably not the most interesting thing, but you can't get very far anaerobically with even carbohydrate. You have to finish that story aerobically. Does that mean your fuel in the exercise itself is the same as the total net expenditure? No. So in the case of Marty's work and high intensity stuff, yeah, in the actual exercise bout itself, you're going to be well above anaerobic threshold. You're going to be well above an RER of 1.0, right? You're going to get really, really... In fact, we have seen many times 1.3s, 1.4s, right, for RERs or RQs. That's mathematically impossible. 1.0 means 100%. So what you mean is like the carbon dioxide expenditure is so exceeding aerobic or oxidative intake that your numbers get like astronomically high. So yes, but that said, anything you just burn there that's sitting either in lactate or in pyruvate or some other intermediate form there, it's going to be finished in the mitochondria with oxidation. You want to recover faster? And I'm talking about within the minutes to hours post-exercise as well as a couple of days. Now this is an aerobic capacity issue. That's how you handle these things. For our athletes that fight in five five-minute rounds, like in the UFC, or we do 12 rounds in boxing, whatever the case is, there is a huge aerobic component to that. Huge, despite the fact that they are going as hard as possible. They are pegged heart rate wise and other things. Getting them to recover, especially from session to session, the morning workout to the evening workout, the higher functioning aerobic capacity we have there—and I don't mean VO2 max per se there, I truly mean aerobic capacity—that is a huge component of their ability to recover and to not be completely trashed the next day. The ones that are really, really smashed anaerobically, like really high, they can't train as much. We have to back them off more. The volume has to be lower. We have to be really strategic. We run into injuries more frequently. We run into just physiologically running into the ground. Our recovery metrics get lower. The taper has to be longer. We have to just make adjustments with calories. They can't handle as much. The ones that are higher in aerobic fitness, they can handle things more. There's consequences of that too, but yeah, you can pick the highest intensity thing you could possibly do, and there's still... Anaerobic and aerobic is not two different things. It's the same gear. It's the top side and bottom side of the same gear. They're not different units. They're just the front side and the back side of that. They will always complement each other. They're not distinct things.

Rhonda Patrick: Right. No, it's true. I mean, but people like to kind of put things in bins. I think Lane explained this in a good way, how people just put things in bins, like it's this bin or this bin. It's rarely how physiology works.

Andy Galpin: It's rarely how physiology works. We have redundant systems on purpose.

Rhonda Patrick: I kind of wanted to ask you just because we were talking about the timing of... We talked about the anabolic window for carbohydrates, how there truly does seem to be an importance there with respect to at least if you're doing more endurance type of training and you want to be ready for the next day. But protein, you know, Stu Phillips has been on, Luke Van Loon, you're in agreement that really the anabolic window is more of a... It's more of the total daily protein intake, right?

Andy Galpin: Yeah, and honestly, that comes down, though, to practicality. It's just simply because I said earlier, it's just really hard to get 400 grams of protein in a day. So you just end up having to do protein like all of the... yeah. Right. Look at Mike Ormsby's work out of Florida State. He's done all that pre-bed carbohydrate stuff or protein ingestion stuff. So it's like 40 grams of protein 30 minutes before bed. Now, in all that stuff, he hasn't shown these huge massive benefits to it. He actually doesn't show any consequences either. So you don't compromise fat, you don't gain more fat, you don't reduce fat oxidation by having this big bolus of protein right before bed. And so the way he will package that is to say if you're struggling to hit your total protein numbers, this is just another window to get you there. If your protein numbers are fine, though, there's no added benefit, there's no huge win. And so that just is another example, I think, at this point, when it comes to the protein game, probably what Lane was saying, like if this is just maybe a way for you to smack in 15 more grams or 20 or 40, then great. But outside of that, there's no magic benefit.

Rhonda Patrick: Yeah, Luke Van Loon actually did a few studies. I don't know if he collaborated with the person just mentioned, but also on this pre, like pre-sleep protein loading where it's like they're giving people protein, a bolus of protein right before bed, and it does increase muscle protein synthesis while they're sleeping. And it, you know, again, I think the way he also framed it was you're, you're getting more of your total protein. You're getting more of that, you know, total protein for the day. But also it seems to make a difference for like elderly people who are just terrible at getting, making meeting that protein r

Luke Van Loon actually did a few studies. I don't know if he collaborated with the person just mentioned, but also on this pre-sleep protein loading where it's like they're giving people protein, a bowl of protein right before bed, and it does increase muscle protein synthesis while they're sleeping. And again, I think the way he also framed it was you're getting more of your total protein—you're getting more of that total protein for the day, but also it seems to make a difference for elderly people who are just terrible at meeting that protein requirement for whatever reason. I don't know. It's just hard to chew food or their appetite isn't—they don't have, their appetite hormones are kind of dysregulated, whatever the reason. So what I wanted to ask you about, because it was kind of interesting, I saw a study you were a co-author on with respect to protein, kind of on that sort of same token, people meeting—it's hard for some people to take in 1.6 grams per kilogram body weight or more, right? Tough. So they're taking protein powders, they're doing the protein powder. It's the easiest thing, right? What are your thoughts on whole foods versus powders? Now you published an interesting study on egg white powder versus the whole egg.

Andy Galpin: Yeah, yeah.

Rhonda Patrick: But I'd love to know your thoughts in general.

Andy Galpin: Yeah, that was actually a pretty cool study. Whole food is always the answer, right? That is always our default position. If we ever have to go to supplements or even supplemental food, like a protein powder or a powdered carbohydrate, that is our second choice, full stop right there. That particular paper and actually set of studies on that found basically the same thing. So whole egg versus egg white, and it turns out potentially we don't have mechanisms behind this, but potentially some of the stuff that's in the egg yolk itself was contributing to additional muscle growth, micronutrient-wise, vitamin D, right, of course, and any number of things that are in there. Absolutely, right? Whether those actually were the case—and again, we didn't have mechanism on them—it was just sort of like, "Why do you think this is happening, even when you match it for calories?" Seems to be the case nonetheless. So to back out your question, yeah, it's a whole food answer, right? If we can get there with whole food—I will say this: we have many of our professional athletes that take almost no supplements, and they definitely don't supplement protein powder. Some of them don't like it—it doesn't sit well with their GI. You don't have to have protein powder ever. I can't think of a compelling reason why, outside of practical, easier flavor, taste, whatever. So protein very specifically, whole food. Muscle growth, whole food. There are other use cases for other supplements and other strategies, but that is our answer, and I think that paper you're referring to showed the same thing.

Rhonda Patrick: Yeah, I was a little shocked, to be honest, because protein was equated, calories were equated, and they were training, and it's like the people eating the whole eggs had increases—I guess it was slight—in muscle mass.

Andy Galpin: Well, it was. Strength also, right?

Rhonda Patrick: Strength also, right. Yeah, but you would anticipate it to be slight. How much of a benefit would a couple of egg yolks a day plausibly give a healthy person? It shouldn't be much. Had those data come back and it was more than that, I would have been like, "I don't know about that." Yeah, well, it's a little interesting because you always think about, well, leucine is the major signal for protein synthesis, muscle protein synthesis, and you would think, "Well, if it's the leucine in the egg white powder, why is there a difference?" Right?

Andy Galpin: Well, again, this is what—like, it's actually funny because when the reviewers came back, it was like I knew it was going to happen. Everybody knew. And it was that, right? You're just like, "Okay, how?" We're like, "Well, I don't know. We don't have this." And so you just start making, as you mentioned, choline, and you start making, like, "Well, plausible this, plausibly that," and then plausibly that. Well, there's also some omega-3s in eggs, and you might think, well, the cell membranes—now maybe the transporters are getting more leucine in. Who knows? Totally. Who knows, right?

Rhonda Patrick: But I personally, you know, I don't like protein powders, to be honest, and it's a processed food. I mean, you look at protein powders, and it's never just protein—never. And so I have every reason to be motivated to eat my turkey burger, my homemade turkey burger, you know, versus the protein powder. But I get it. I get, like, I have these pre-made homemade turkey burgers—they're food prepped, and they're there, ready to just microwave. I'm not scared of microwaves, so easy for me to do. But there's a lot of people that it's like, "Ah, they're not going to cook something." If they don't meal prep, then it's the go-to, right? You're going, "I don't like protein bars." Same thing, where it's like, it's processed, it's all this stuff. So I kind of liked the little extra motivation to say, "Yeah, go for the whole foods. Go for the whole foods," you know.

Andy Galpin: I have had a love-hate relationship with those things as well—spent many decades smashing many scoops of protein powder a day, and then probably went a decade or more with almost no protein powder. Now I'm back on it a little bit more for other reasons, like they're getting better with some of those things. But if you're asking me what I'd rather do—have a candy bar or have, like, a piece of whole food—I'm always going to take the whole food for preference, just flavor preferences. Like, I like eating food more than I like supplements.

Rhonda Patrick: So we talked a lot about macronutrients. I think there was, you know—I didn't know if there was—going back to the fat, just before we move on to the micronutrients, is there really an optimal fat ratio or timing? I mean, or is it mostly come down to if they perform better, if that's what they want, or do you think that it's something that's just not as important as carbohydrates?

Andy Galpin: Well, I'll answer this two ways. I'll be short. I actually think it's an interesting question—I don't think people spend a lot of time studying it. I'm open to the possibility that there is way more important in different timing scenarios than we think, but that people just have not done that work. So that's an open-ended question that's never been there. The other way I'll say it is because of that, I guess, yeah—I just don't feel like at this point we have any compelling reason to think that it is a critical thing to pay attention to in terms of timing and stuff relative there. If you just think about plausibly what these different fueling sources are intending to do, it makes sense that fat is probably the thing you should be third concerned about. You have backup stores of it already, it can be mobilized when you ingest it, or you're using endogenous fat—it still happens at roughly the same rate, so on and so forth. So with all that, I think that's our answer, but I'm open. I'm open to other things.

Rhonda Patrick: What about—you mentioned earlier that you're mostly concerned if people aren't getting enough fat, and so I'd love for you to explain to people why that is, but also I'm interested in your thoughts about the quality of fat. Are some fats better than others? Do some fats hinder performance?

Andy Galpin: Yeah, this is actually a whole category of questions that are super interesting. We grew up in the same nutritional generation—right? Low-fat, low-fat, low-fat. And then we saw those consequences. Okay, if you are really low fat for a long time, there are a cataclysm of problems that can happen with that—especially if you're combining that on top of hypocalorism: endocrine disruptions, sleep disruptions, probably long-term health disruptions in many areas. It's going to be a huge issue. What does low mean? I don't think we have a great definitive number on that, but if it's less than 10% of your calories, again combined with hypocaloric for a long period of time, then you're probably running into all kinds of issues—from cell membrane, like, you don't have the basic building blocks to keep cells together, to the other ones: endocrine health, organ health, transporter health, storage health—it has so many roles in our body. So you want to stay away from those things. Now, past that, in terms of fat quality—boy, how inflamed... Your audience is probably a little bit better, but how mad do you want the internet to get about these following statements, right?

Rhonda Patrick: The truth is all that matters to me. Yeah, let's hear it.

Andy Galpin: All I know matters to you. You've been clear in your career of how you approach things, but there's just not a lot of compelling evidence that whole fat in itself can be disregarded as always healthy or always bad. So animal fat, vegetable fats, seed oils—we'll throw it out there—when managed under all proper situations, we're okay here. Like, we're really just okay. You're fine. We're going to handle these things. But you go exaggerating any one of those areas, you're going to run into problems, right? So if you're eating copious amounts of saturated fat and combining that with low physical activity, hypercalorism, you're going to have problems. Same thing with seed oils, right? You cook them, you process them, you do all those things—you're going to run into problems there too. So what does a quality fat mean? I always default back to the same thing: I don't want to eat anything that's processed. I don't care—animal, plant, you pick it. I'm trying to eat whole food versions of everything, and that is true for my carbohydrates, my proteins, and my fats. So we don't approach the fats that differently. So I don't deal with it that much because rarely are we going out of our way to give people processed foods—processed fats included. So when we're eating—for most of our people, they eat animal sources, right? So we're going to be getting fats from animals in a reasonable amount, and we're paying attention to those other factors—vegetables, protein, whole foods. So because of that, animal fat just doesn't come in huge quantities—we don't have the physical space—it comes in a normal amount, and we're okay. At the same time, we're not having to be so guarded against seed oils because we're not consuming most foods that come with seed oils—we don't have to worry about that.

Rhonda Patrick: Right, it's the company.

Andy Galpin: It's the company, right? These things are not critically—I know some people get so fired up about it.

Rhonda Patrick: What about olive oil, avocado oil, avocados, nuts? I mean, omega-3 fatty acids, fish—those are all...

Andy Galpin: If it's in a whole food, we have no issue with it, right? You have to be a little bit careful with exogenous oils, just because, as you're aware, caloric intake just gets really, really high there. But do we have our people eat nuts? Yeah. Avocados? Yes. Like, all of the above. Whole foods are almost always going to be on our list. You just be careful with additives—like, you put something into an oil in low quality, in the sunlight—fill in the blank there. Same thing with nuts, right? Those can come in low quality as well. So we always try to get those things in the appropriate standards, and then we don't have any issues past that. So I don't know how much we've successfully dodged or didn't dodge any landmines on that one, but man, I just don't have a lot of aptitude for—

Rhonda Patrick: I mean, we'd have to spend hours talking about it because it's so much nuance. That would be a whole other—

Andy Galpin: Thank you for saying that so I didn't have to say it. That's one kind way to put it, but my goodness, people.

Rhonda Patrick: Yeah, there's a lot of emotions involved in nutrition, for sure.

Andy Galpin: That's a great way to put it. There's a lot of emotions involved.

Rhonda Patrick: So micronutrients…